How China & Korea Became Leaders in Electric Vehicle Exports

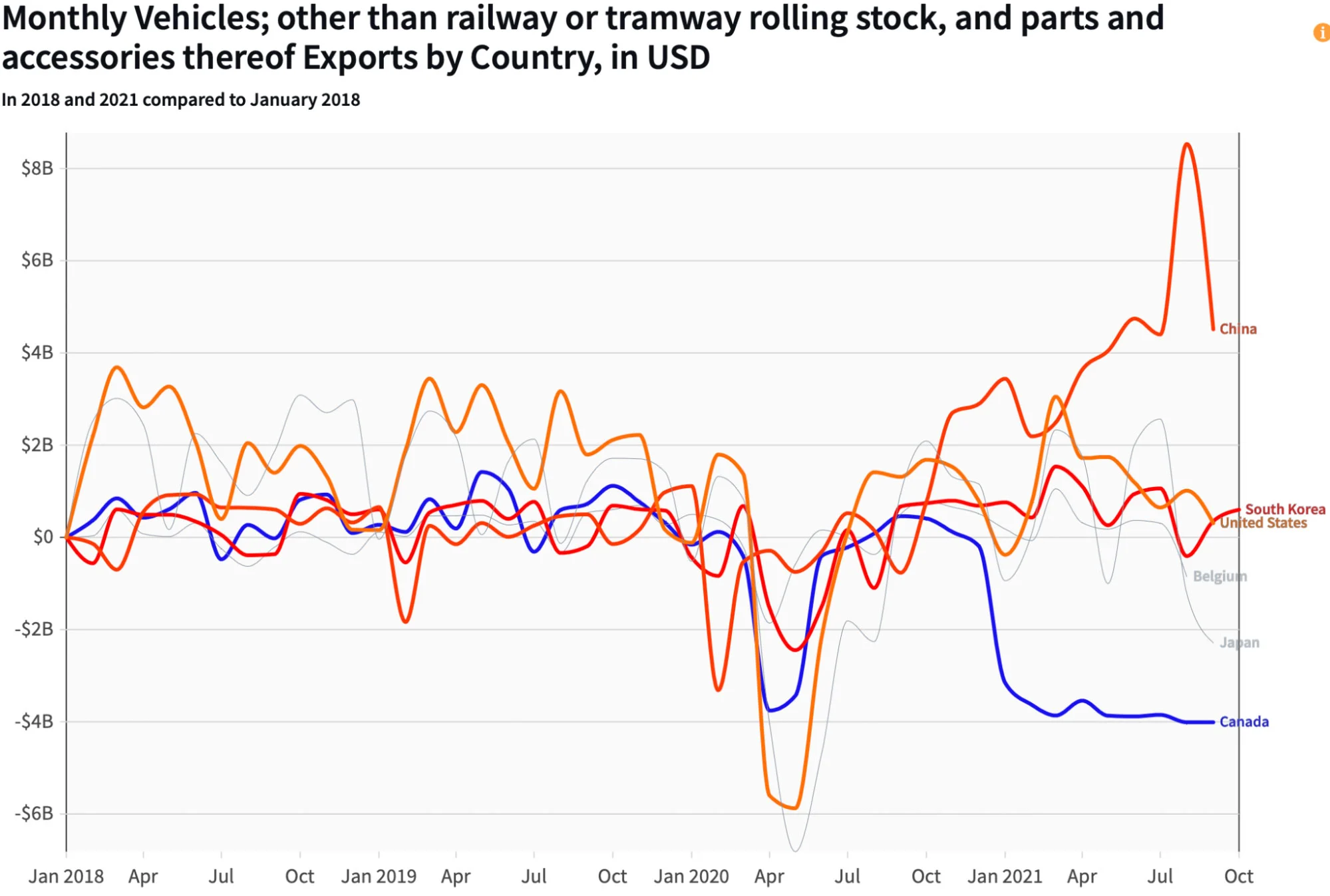

Electric Vehicles and associated supply chains are a crucial technology where the United States' lead has, in the past decade, moved to China and South Korea. Understanding how this happened is essential to developing other areas of essential innovation for a net-zero economy.

On December 9, 2008, the Mercury Times covered a noteworthy milestone for a Silicon Valley start-up: its 100th product delivered. The occasion was so memorable that the company's CEO personally handed the keys to someone then "known nationally for being the man Oprah Winfrey clung to during President-elect Barack Obama's victory speech." The new car, the Roadster, was "something that's sexy and fast and fun, and that's also environmentally responsible," stated company’s CEO, Elon Musk, to reporters. Thirteen years later, that sexy and fast and fun car from the Valley is the foundation of a trillion-dollar company.

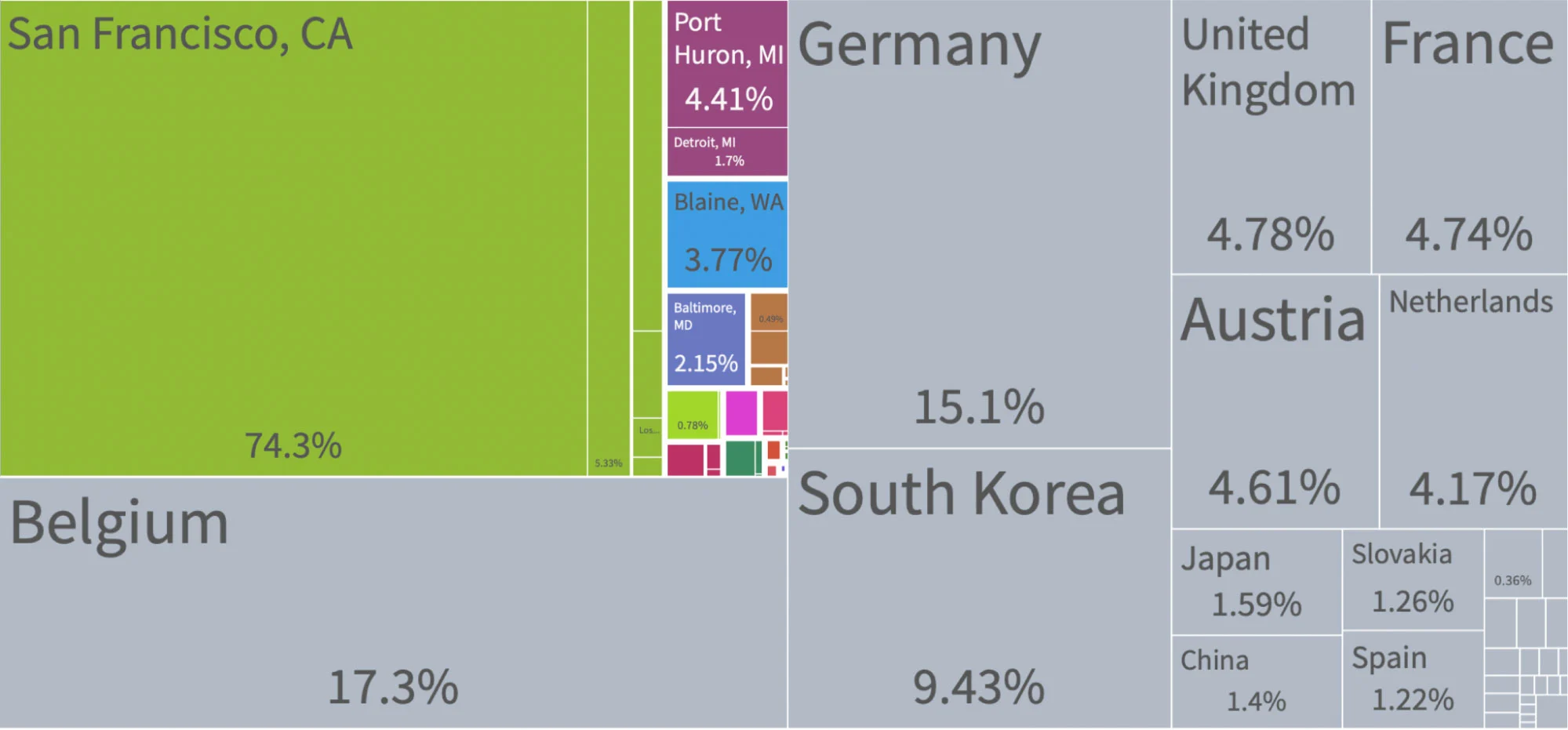

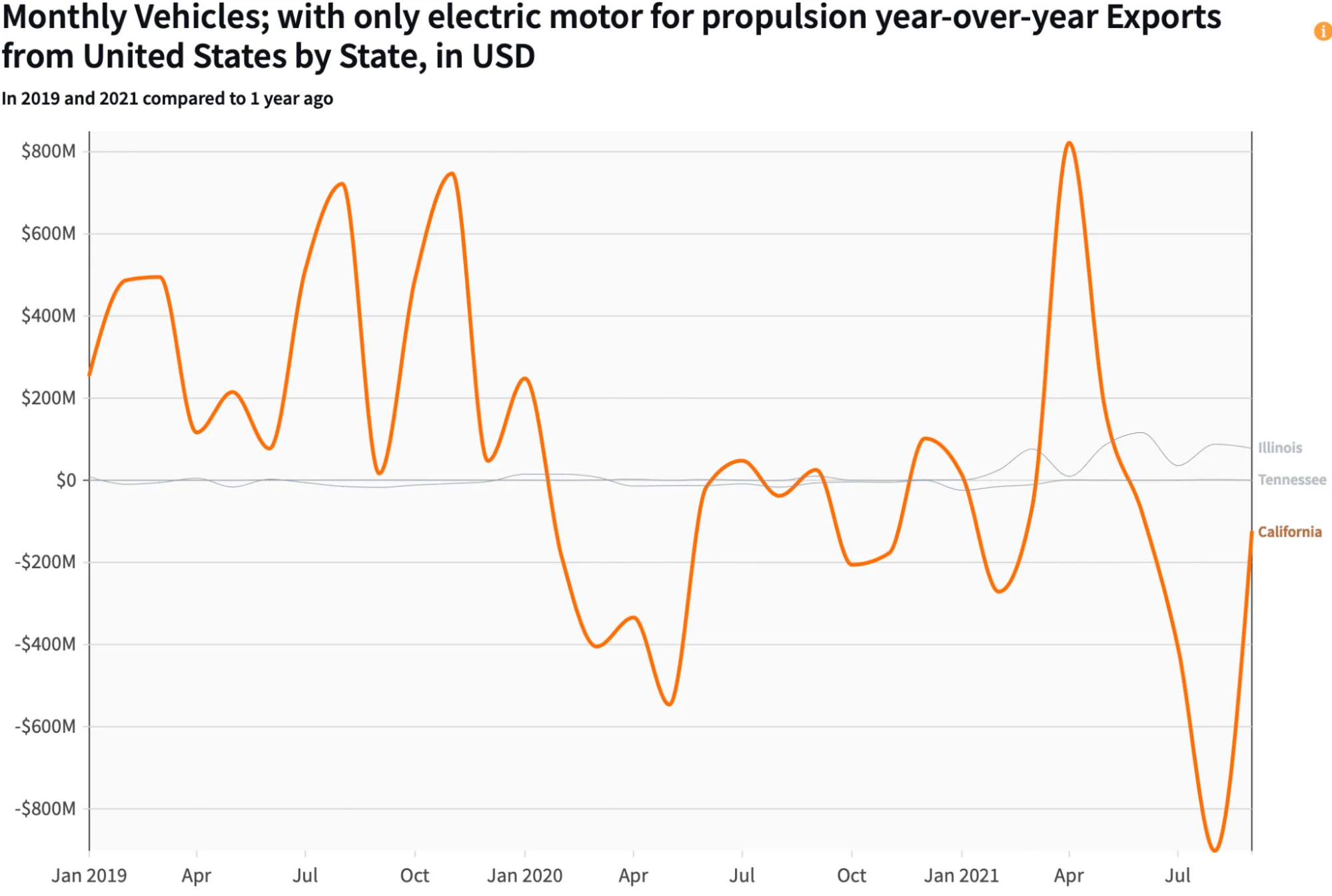

Tesla's success in disrupting the automotive industry gave the U.S. an early lead in EV exports that lasted for over a decade. In 2019, for example, close to a third of the $24.9B in EV global exports were shipped from California.

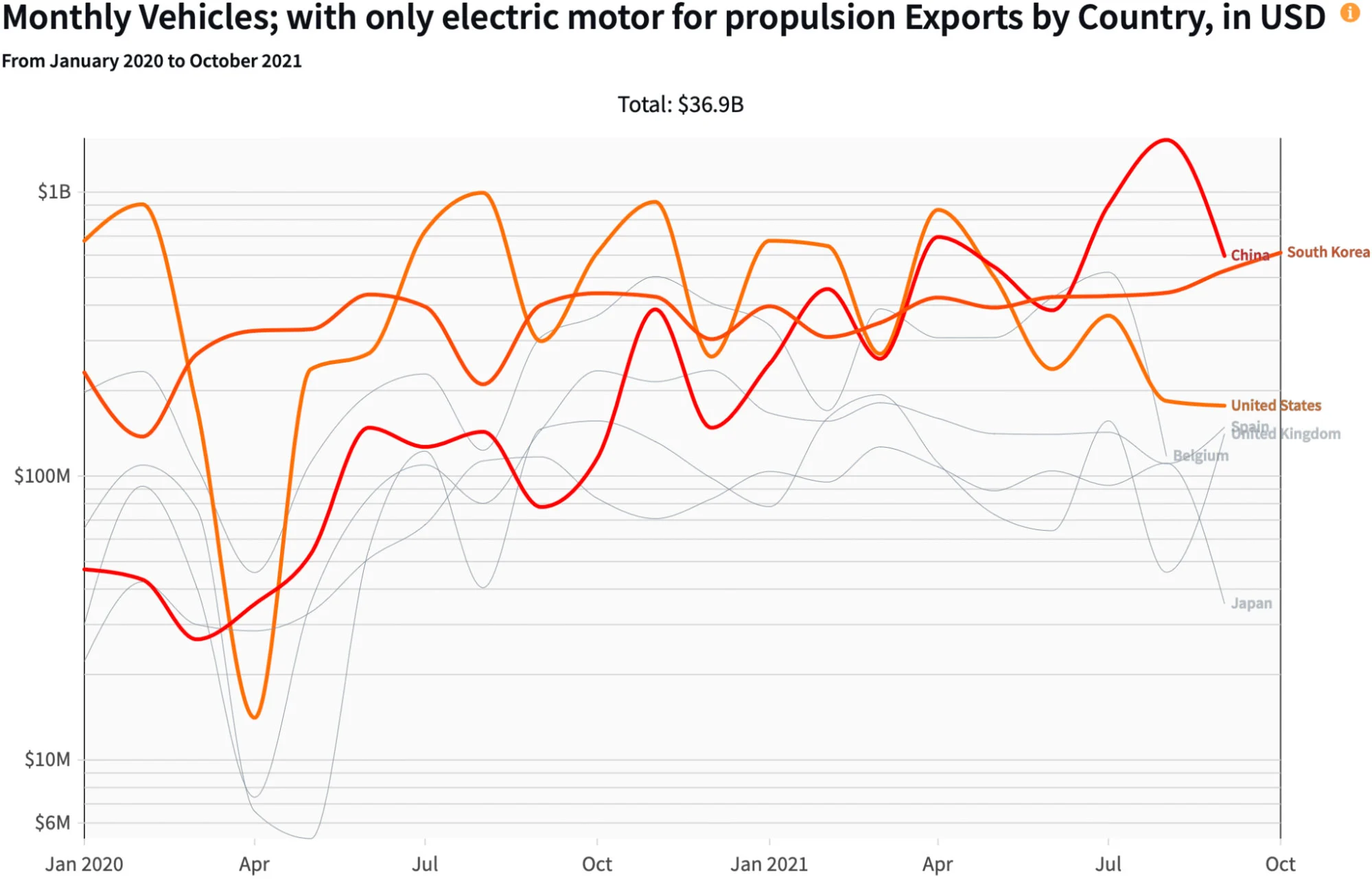

For 2021, however, American EV export dominance may no longer hold.

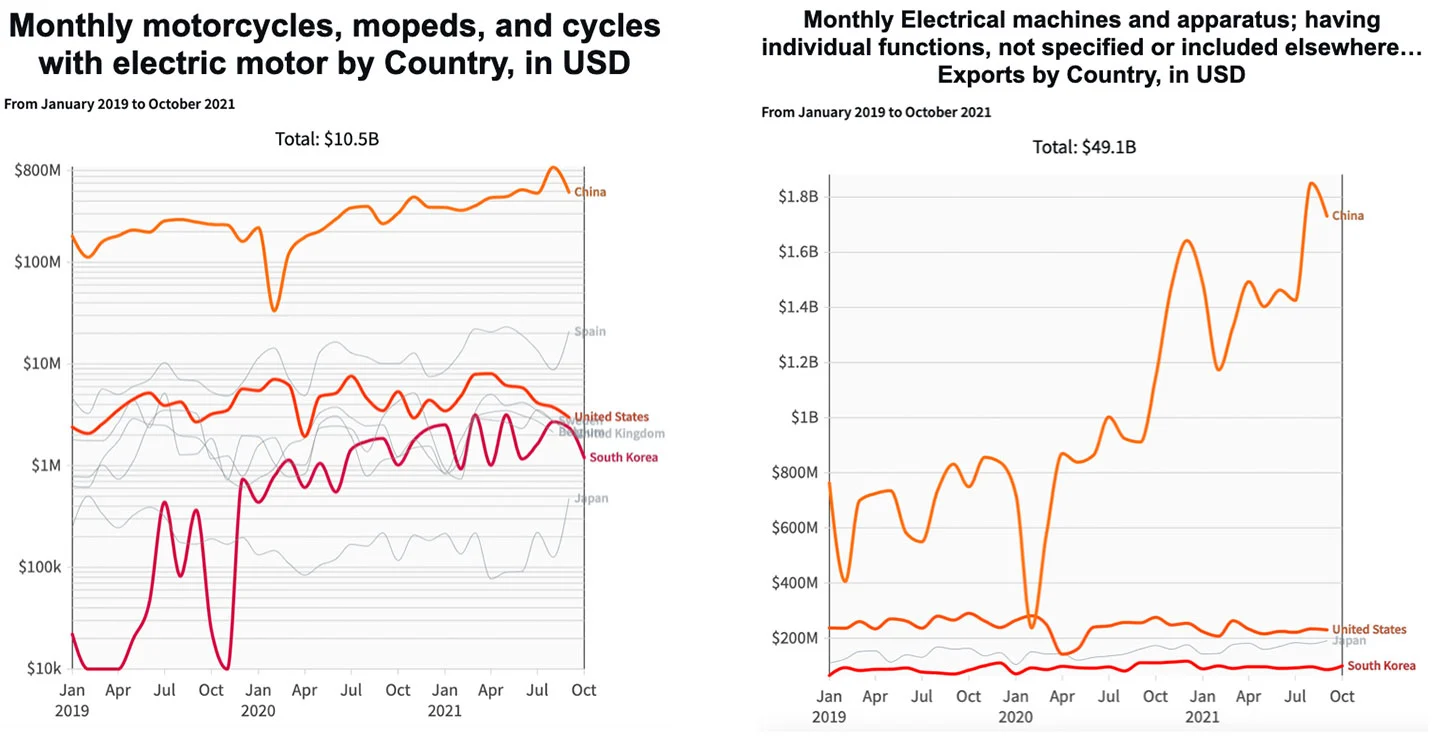

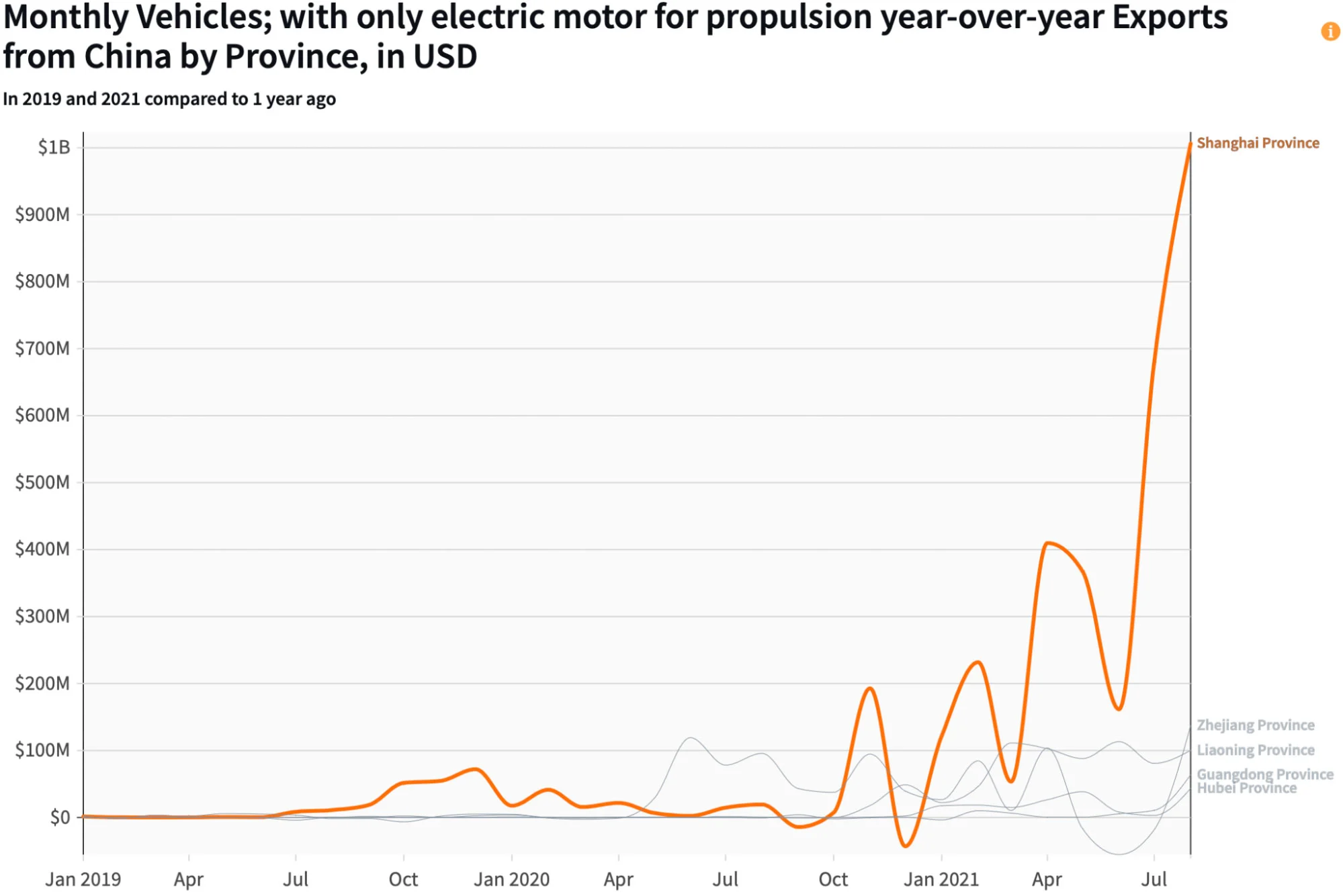

Recent trade data suggests that at the end of 2021, there will be more EVs shipped from China and South Korea than from the U.S. Last August alone, China exported a record $1.5B in electric cars, double what the U.S. exported in all of Q3. In September, South Korea exported 298% more than the U.S. How did this dramatic change in EV exports happen?

The advent of EVs provided Tesla the rare opportunity to challenge the automotive establishment. For starters, Tesla was able to build fun cars to drive and pack them with the feature that would disrupt an entire industry: a supply chain to deliver batteries to travel long distances and recharge quickly.

Tesla's challenge to the automotive establishment motivated some governments to take aggressive EV policies, helping emerging companies, technologies, and business models to change an industry defined by the urgency of technological breakthroughs. The story of electric cars is therefore essential as it highlights the opportunities and shortcomings in the world's ability to accelerate the clean energy transition.

This story begins four years before the man then known for his brief interaction with Oprah Winfrey and President-elect Barack Obama got the keys of the 100th Roadster. And, like many other origin stories, it takes place in California.

Early days in the Golden State

In 2004, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) tried something new in its efforts to incentivize the production of zero-emission vehicles (ZEV): it created a regulatory system –later adopted by other states– that offered $7,000 in credits for ZEV. This approach came after more than a decade of mandates that didn’t grab the attention of manufacturers to develop the technology and of consumers to demand something other than internal combustion cars (ICC).

The new system had the benefits of being more market-friendly, as consumers could get a better deal for buying ZEV and automakers an incentive to design them. Then, a few years later, the credit scheme got a push, as President Obama announced a tax credit of up to $7,500 as part of a $2.4 billion in fundingto motivate car companies to build more electric vehicles. So in 2009, California residents could get $14,500 in federal and state credits to buy an EV. But was this enough of an incentive to make the Roadster competitive?

The Roadster was a revolutionary car: the first all-electric vehicle to use lithium-ion battery cells to be considered highway legal. It was also fun (0 to 60 mph in 3.7, top speed of 125 mph) and cool (George Clooney and Leonardo DiCaprio owned Roadsters). The only problem was its cost. The price tag was $109,000, and Tesla had to take a $100,000 loss on every Roadster sold. Given this cost structure, $14,500 in credits didn’t make much of a dent in consumers or Tesla.

Automakers rely on supply chains to reduce costs. For example, if existing manufacturers were looking for ICC components, they had plenty of options. But there was no existing supply chain for many of the EV components. The main challenge to making affordable EVs was not the car but its battery: it was too expensive, and few companies around the globe were making them. In 2007, a lithium-ion battery cell cost more than the rest of the car and only lasted about 80 miles.

Tesla was struggling. In 2010, the company got a life line in the form of a $465 million loan from an Energy Department program to fund car companies making fuel-efficient cars, giving Tesla more time to figure out how to make an affordable car for a profit. Around this time, Tesla estimated that ramping up production to 500,000 vehicles per year would require the entire worldwide supply of lithium-ion batteries available.

Out of necessity, in 2014, the company built a Gigafactory in Nevada to supply enough batteries to support demand, taking advantage of $1.3 billion in local tax breaks. Tesla’s approach is in many ways a “throwback to the early days of the automobile, when Ford owned its own steel plants and rubber plantations”. It took Tesla years and taxpayers billions of dollars in incentives, loans, and subsidies to get a battery that could last 300 miles.

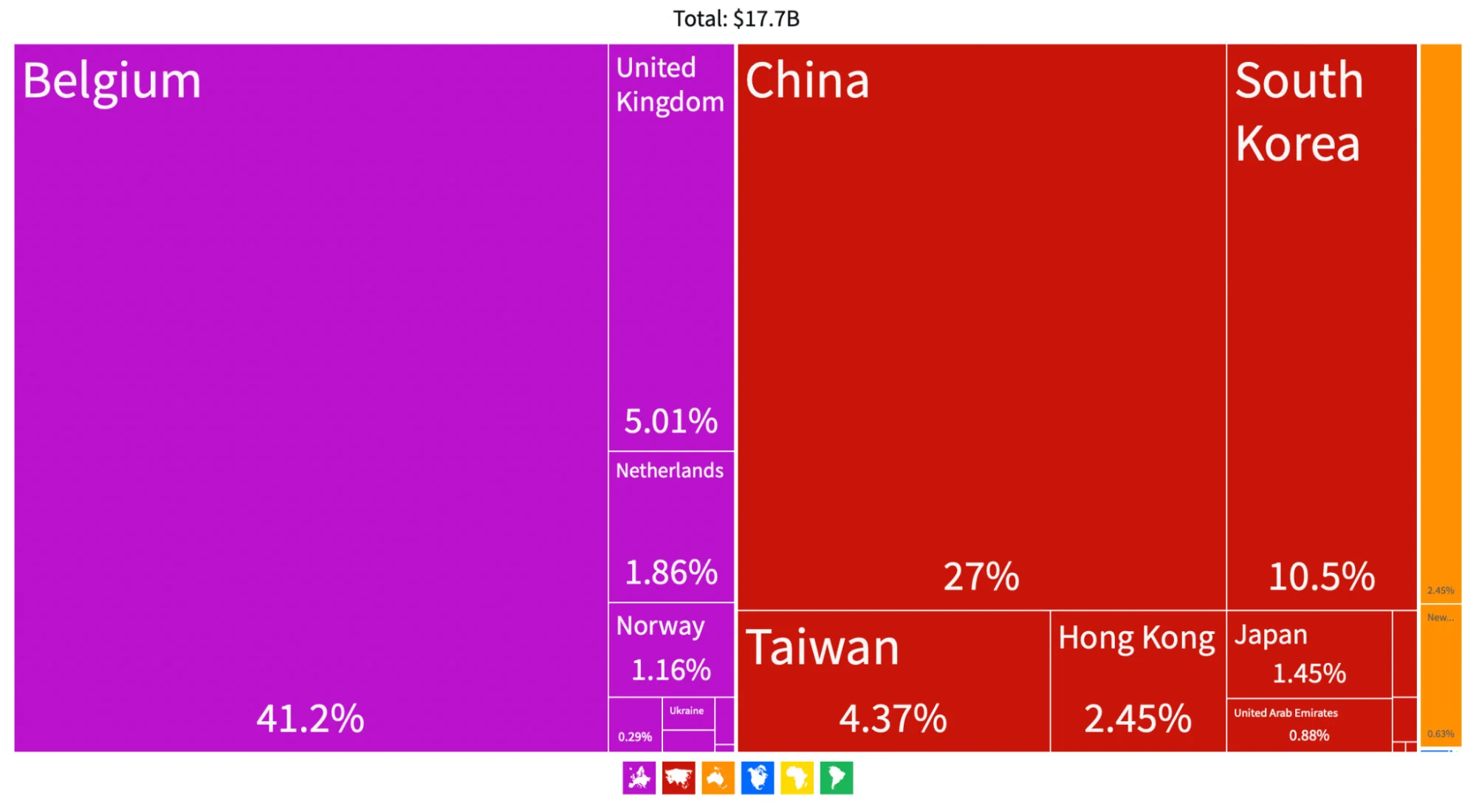

There was no route, but Tesla's talent is not the only reason for California's early EV success. State and federal subsidies, regulations, and credits were essential. That's why there are fourteen EV companies in Silicon Valley, and $17.7B in EV exports to 64 countries over the past five years.

Tesla's success in disrupting the industry gave the U.S. an early lead in the race to provide the global market with the cars we now rely on to tackle climate change. Even in 2008, it was a safe bet that consumers would eventually swap their gasoline cars for electric vehicles. Electrified transport, in some form, was already seen as part of our future by the California Air Resources Board (CARB), Roadster’s owners, Tesla’s investors and team, and others. But how much and for how long would they have to wait for the bet to pay off? Years? Decades?

Bureaucrats around the globe noticed how the industry had changed and decided to use the opportunity to leapfrog in the new enterprise. Their objective was to use different government tools at their disposal to pave the road for developing low-cost family electric cars and, one day, beat the U.S. in vehicle manufacturing.

China and South Korea jump into the race at full speed

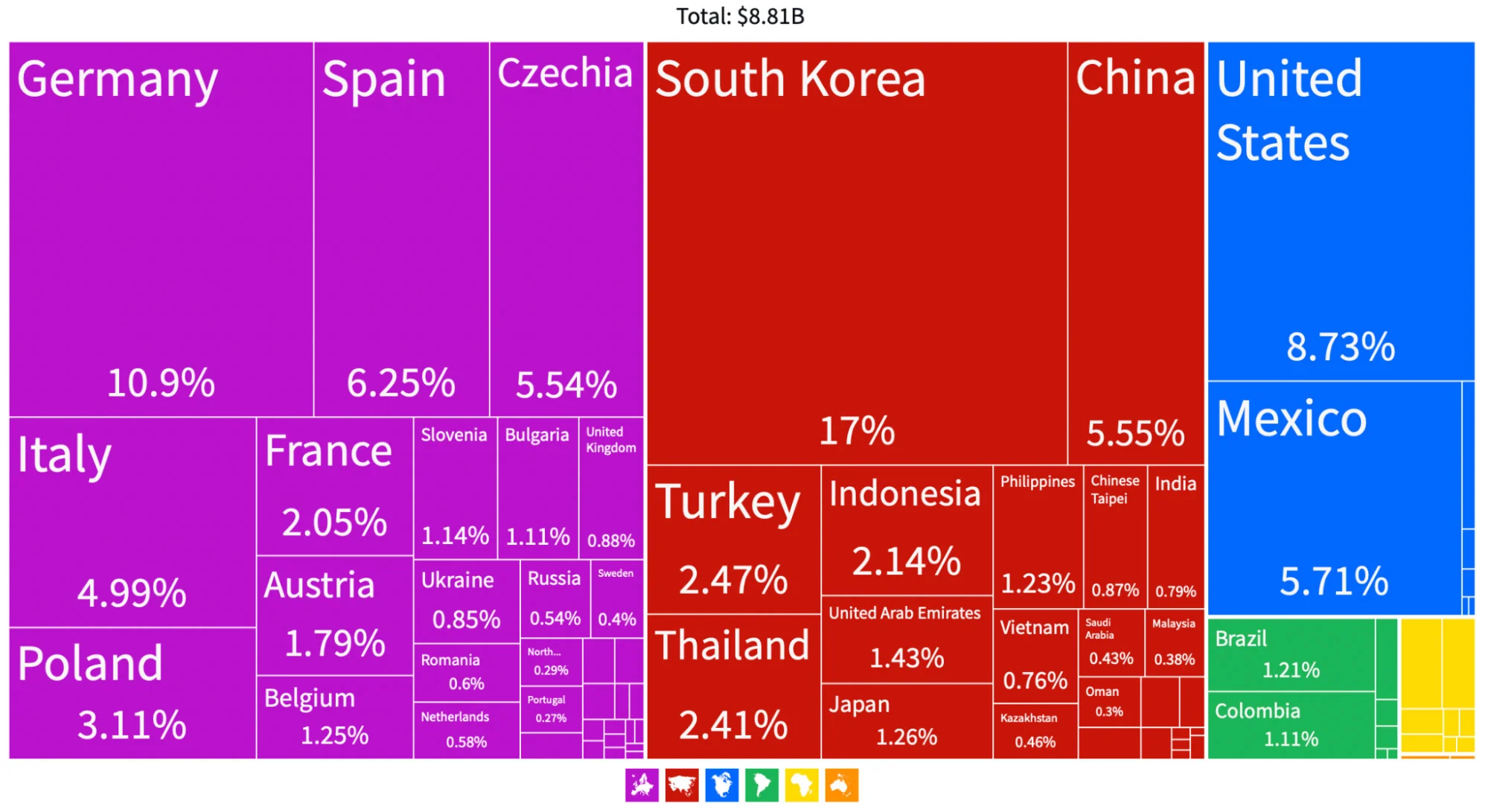

The same year Tesla was delivering the 100th Roadster, the Chinese and South Korean governments announced plans to swamp the roads with electric mobility products. They used two broad avenues: incentives for a nascent, high-tech industry and investment to build the infrastructure for consumers to transition from internal combustion to electric mobility. After a few years, their plans worked.

In 2018, of the 1.5 million EVs sold globally, 1.2 million ended up on the roads of China and South Korea.

The difference in the industrial policies between the U.S. and these two countries is that China and South Korea articulated a clear, consistent, and coordinated vision for a national industrial strategy that included manufacturing EVs, batteries, and building infrastructure. Moreover, they chose EVs as the centerpiece of their plans to jump-start their auto industries. Although each country used policy tools based on its competitive advantages and unique mobility needs, their unifying goal was to get ahead in zero emissions transportation.

In China, for example, the National Bureau of Statistics (CNBS) calculated, in 2008, that one dollar of investment in the domestic auto manufacturing industry would drive 2.64 dollars of value-add in related upstream and downstream sectors. In addition, government policies consider electric mobility a driver of other supply chains relevant for the energy transition.

Electric mobility plays an essential role in the transportation disruption in all vehicle segments. Driving more EVs to market is only one component of electric mobility's fast, widespread adoption: E-bikes, electric motorbikes, e-buses, and e-trucks are also vital. In all these transportation products, the standard features are: entirely or partly driven electrically, stores energy onboard, and gets its energy mainly from the power grid.

In 2016, over half a million electric cars were sold in China — more than double the number of electric car sales worldwide. Sales of electric cars in China rose 53% in 2016, compared to 37% growth in the rest of the world. The world’s largest EV market (3.81 million cars in 2019) provides China's automobile industry a first-mover advantage and scale. And the bigger you get, the lower your costs, thus the more advantage you have. And once your economy goes down that path, it's easy to get locked into dominating entire markets.

In 2020, the top of China’s sales list was Wuling’s $4,200 mini-EV, the cheapest EV in China (made in partnership with General Motors), and Tesla’s Model 3, now built-in Shanghai.

Tesla’s factory in Shanghai now produces more cars than its plant in California. In one month, the province of Shanghai exported a third of the EV shipped from California in all 2021. Now, even Tesla’s exporting more EVs made in China than in the U.S., including Model 3 vehicles.

China and South Korea are increasing EV exports by leapfrogging into the forefront of a race no longer constrained to manufacture EVs, but cars.

The Road Ahead

Electric Vehicles show that it’s time to get serious about industrial policies. It is not about picking individual firms or even narrow technologies. Instead, it is about focusing on broad technology areas and industries that we know will be important when determining winners and losers.

A country can't settle on selling only commodities and natural resources. Even if you can afford to buy more complex products (like electric vehicles) from overseas by selling soybeans, natural gas, and oil, this isn't the best option when climate change, consumer behavior, and technology have made electric mobility the only way to power our future.

In a world where many countries compete heavily for competitive advantage through active government policies, it is naive to think that a country can thrive in a new industry without having its own set of policies to win the global market. The idea that some governments have industrial policies and others have free markets is absurd. All governments favor some economic sectors. The critical questions are: How can a country leapfrog competitors into the forefront to develop next-generation technologies? How can you improve industrial policy for other economically essential innovation areas?

When the race was about internal combustion cars, the first 100th product delivered by a startup was indeed noteworthy. From now on, it’s all about electric cars.

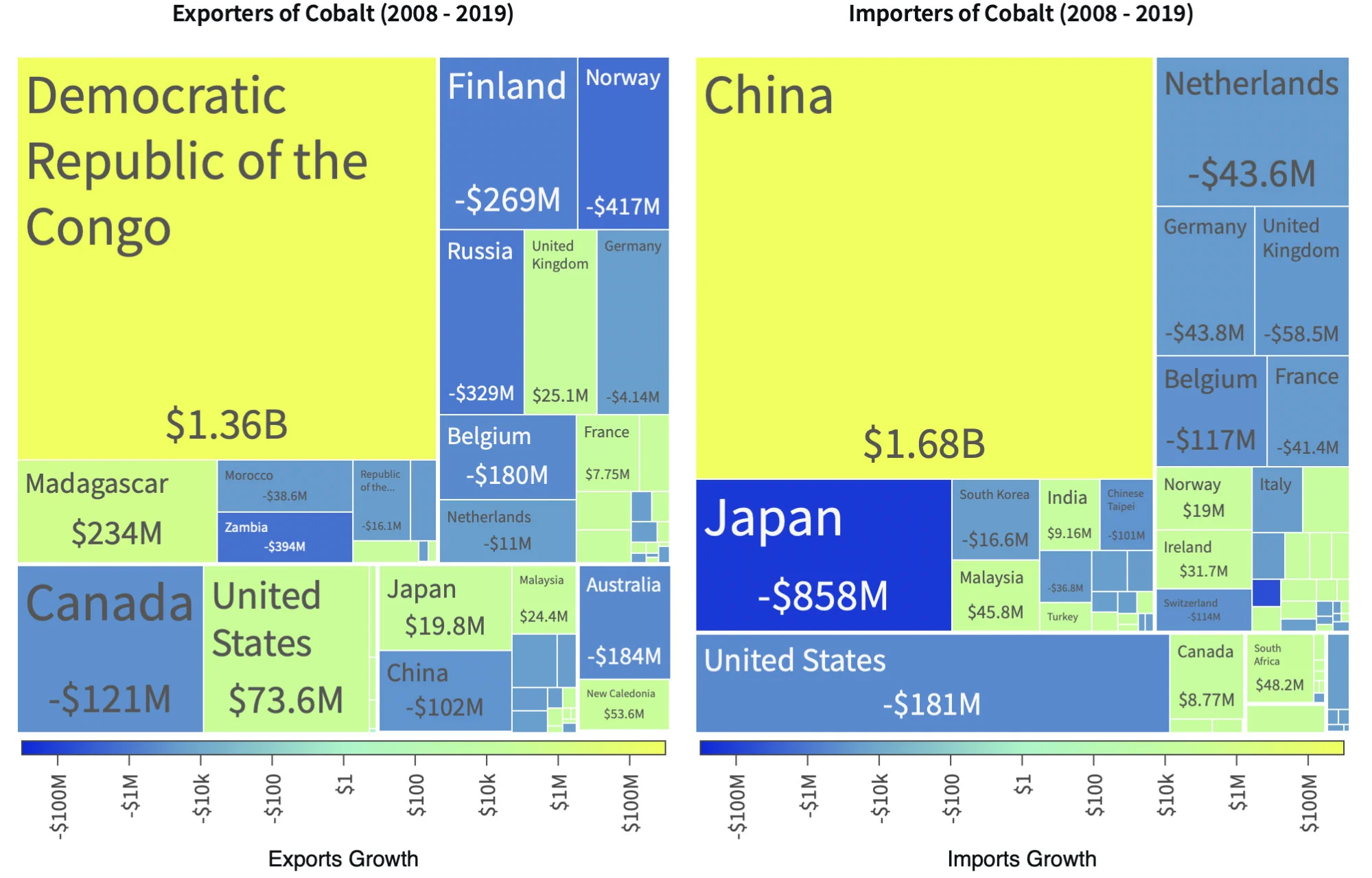

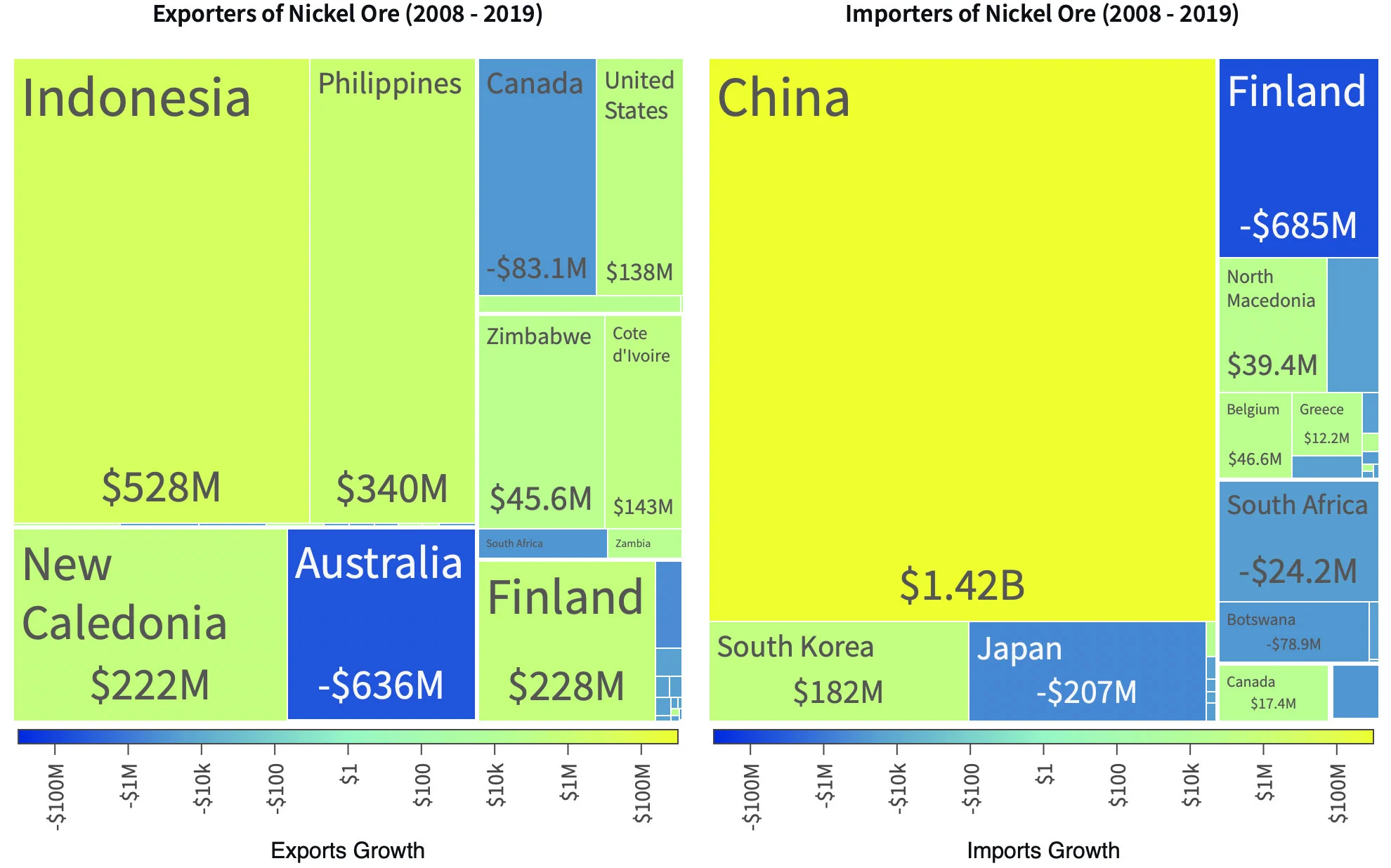

One of China’s key EVs policy features was a combination of central and provincial subsidies of up to $20,000 per car, focusing on small, affordable models –in contrast to the U.S., where EV sales are predominantly premium Tesla models. Additionally, the central government took steps to promote Chinese suppliers of batteries, including gaining access to essential raw materials (e.g., lithium, cobalt, and nickel). Furthermore, Chinese banks enabled Chinese companies to acquire mines in Africa, Australia, and South America, developing a vast influence network over the most challenging links in the EVs supply chain.